Submitted by

Paula Vitaris

Review of A Matter of Life and Death (1946)

and Age of Consent (1969)

The Sony DVDs

Reviewed in Video Watchdog,

No. 150, Summer 2009

THE FILMS OF MICHAEL POWELL

A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH (107m 7s)

AGE OF CONSENT (106m 24s)

1946/1969, Sony, $20.96 DVD

By Michael Barrett

This set pairs a great popular success of 1940s fantasy with a widely unseen film about beauty, sex and art. After J. Arthur Rank's gong. A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH begins with the target logo for the Archers (the writing, producing and directing team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger) shading from black and white to glorious color, the manner in which the film to follow will distinguish the lushness of life from the stark absolutes of death.

In lush Technicolor, squadron leader Peter Carter (David Niven), an RAF pilot in the final days of WWII, bails out of his plane before it crashes. He lands in the ocean and awakens unharmed on a beach, where at first he assumes he's in Heaven and asks directions of a faunish naked shepherd playing a flute. Completing his miracle, he runs into June (Kim Hunter), the WAC who talked him through what he assumed to be the last minutes of his life over the radio, and they begin a delirious sylvan interlude. Because of Carter's headaches, vision problems, and hallucinations, June consults Dr. Reeves (Roger Livesey), who is introduced surveying his quaint Canterbury-ish village via camera obscura, a means of vision that's true yet fancifully distorted, even inverted. He diagnoses Carter's brain injury, which requires an operation, and he interprets Carter's ongoing fantasies as psychotic projections that must be entered into and resolved.

So much for realism. Meanwhile, a parallel fantasy narrative is set in a black-and-white vision of Heaven as a bureaucracy in the manner of LILIOM and HERE COMES MR. JORDAN. Reflecting wartime exigencies on Earth, briskly efficient women are running the show. Due to the error of Conductor 71 (Marius Goring), a foppish aristocrat who lost his head during the French Revolution, Cater missed his pick-up. Dispatched to correct the situation. 71 returns to Earth's lush colors, as marked by the transition on a close-up of his rose and his famous remark "One is starved for Technicolor... up there." (As Ian Christie points out in his commentary, the line is partly looped; Goring actually said "One is starved for color up there.") To entice Carter to come along and die quietly, 71 keeps offering him a game of chess - an idea developed by Ingmar Bergman in THE SEVENTH SEAL, whether he saw this picture or not. Instead, Carter files an appeal which will turn on Heaven's negligence and the question of whether his belated love for June in the summer of his life takes precedence over prior claims. The case goes to trial.

Winding up in a courtroom in generally fatal to drama. Even Perry Mason knew the true function of a court is to unmask a killer, not to deliver speeches. Christie notes that this sequence engages contemporary arguments on Britain and America's postwar relations, which this film allegorizes. If this segment is the draggiest, not least due to the blovations of the prosecutor (Raymond Massey), the film never once loses its strangeness, humor and audacity. By the way, this sequence has the only notable defect in a print otherwise marvelously rich and sharp: fluctuations in the white around close-ups of the speakers' heads aren't due to the shifting light effects. Fortunately, the climax gets out of the celestial court for another lovely coup de cinema on the Stairway to Heaven (the film's US title), which bridges our world (or reality) and the next (or fantasy), and neatly summarizes the verdict with a quotation from Sir Walter Scott.

Here is a movie made one year after the end of WWII and without a trace of jingoism or anti-German sentiment (though it doesn't extend to Germans in Heaven). The opening God's-eye-view seems grave about a firebombed German city as well as the potential of "the uranium atom," and Massey castigates England for its empirical warmongering past and present. "Think of India!" he intones. Powell and Pressburger even endorse his vision of America as a multi-cultural beacon of freedom and the world's hope. And, if you really take the film seriously, it's about how the stiff-upper-lip authorities make mistakes and why justice shouldn't be confused with law. No wonder Churchill was annoyed by these guys; their wartime propaganda had been too intelligent for the term, and they didn't let up even during escapist fantasy Still, this film matched the tenet of its times, enjoyed great success, and remains beautiful and thoughtful today.

Are the fantasy parts "true"? The film opens with this notice, to which I've added punctuation: "This is a story of two Worlds, the one we know and another which exists only in the mind of a young airman whose life & imagination have been violently shaped by war. Any resemblance to any other world known or unknown in purely coincidental."

This declares authoritatively that we should accept Reeves' medical rationalizations. Sequences are carefully planned to support the notion that a creative and well-read Carter is hallucinating from what he knows, including his knowledge of Reeves' death. Heaven's monochrome may be the convention, sometimes used in later films, that people dream in black-and-white - although this reverses the convention of Technicolor dream-fantasies such as THE WIZARD OF OZ, and when Carter dreams of angelic encounters on Earth, these are still in color. When he rings the bell after his second encounter with 71, he's still sitting down instead of standing, as though just awakened. June's ambiguous remarks in the final scene don't indicate any knowledge on her part in the trial. A book borrowed by 71 could have been in Carter's jacket all along. Indeed, there's at least one detail - the identity of the chief surgeon - that supports the "realism' theory.

How then did Carter survive his fall? Reeves says even that may be explained, although it never quite is. However, according to Christie, the film was partly inspired by a real-life case of just such a survival. More significantly, given the fantastic elements of the film's "reality" (miracle survival, shepherd faun, camera obscura), it's possible that the entire narrative before the closing scene with June has been one long hallucination of the comatose or medicated pilot and that we've never known the actual situation.

Ironically, a mark of the film's sophistication and subtlety is how easy it is to ignore all that and take its fantasy at face value, which surely many viewers have done and will do. Despite its opening statement, and unlike THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI or THE WIZARD OF OZ, which firmly commit themselves to being All A Dream, this is an early example of a cinematic fantasy that keeps its ambiguities serenely balanced. That's partly because they support each other instead of one interrupting the other.

Meanwhile as with many Powell and Pressburgers, we witness an exuberant, almost Wellesian delight in cinema, in its plastic possibilities of vision, and in color and effects which may serve a narrative purpose or which may intend merely to give us pleasure as they revel in their own joy A making-of would have been a welcome supplement to cover all this. Christie points out some things, such as cinematographer Jack Cardiff's unusually graceful camera movements for a Technicolor film of this era, and which surely got Cardiff the job on Alfred Hitchcock's amazing and underrated UNDER CAPRICORN. Geoffrey Unsworth (2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY) was Cardiff's camera operator and Michael Chorlton provided the thrilling motorbike photography, a technique we take for granted today but which remains beautiful here. Douglas Woolsey and Henry Harris are credited with special effects, with unspecified additional effects by Percy Day. There's a remarkably good walking-through-the-window moment and a startling freeze-frame which might make a modern DVD viewer think a layer-charge is occurring. I would like to know if the camera obscura sequence uses the genuine device, and if not, how that footage was taken; apparently it's matted in. (Some facts and speculation on this topic appear on the website Powell-Pressburger.org)

Production designer Alfred Junge, costume designer Hein Heckroth and editor Reginald Rose also contribute incalculably to the visual beauties, underlined by Allan Gray's score. Amid this technical feast is the intellectual appeal of the film's literary and cultural references, such as poetry quotations, rehearsals of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM (with Mendelssohn's music thereto) and a cameo by John Bunyan, whose PILGRIM'S PROGRESS is one of the film's inspirations. This is all part of the movie's abundant wit, which includes such self-conscious deflations as the "starved for Technicolor" quote and the opening portentous narration about the universe ("Big, isn't it?"), which seem more in the line of Chuck Jones or Tex Avery.

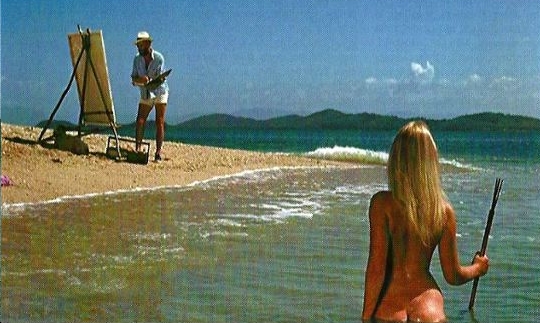

Surgeons race to save a life, as the Stairway to Heaven hovers expectantly

in the Archers' classic, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH.

|

On Disc 2 is AGE OF CONSENT. Co-producer James Mason plays Bradley Morahan, a successful artist fed up with his own success, with the art world, with the city, with other people. He flees New York for Dunk Isle off the Australian coast, where he finds Cora (Helen Mirren), whose name may be intended to evoke coral (as in "of his bones are coral made") and the Great Barrier Reef where she swims. The plotline is a series of incidents with minor characters who are mostly motivated by sexual feelings, and this is meant to contrast with the relationship between Bradley and Cora, Which in not so motivated though he's constantly having her take her clothes off.

On the side of the curdled old misanthrope, the motivation is spiritual and artistic. He has (to his conscious knowledge) no interest in Cora sexually but only in what she represents; nature, purity, the light, the elements, and his owe creative rebirth as visualized by his new, earthy, representational style. (His abstract New York paintings are by John Coburn while the Gaugin-ish island work is by Paul Delprat.)

What Cora finds in all this, besides an opportunity to make money through modeling fees, is a growing awareness of, and confidence in, herself as a person with a young strong body of which she needn't feel ashamed. This contrasts with the poisonous judgments heaped upon her by grandmother Ma Ryan (Neva Carr-Glyn), who compares her with a shameful, lost mother. What some might call Cora's self-actualization and empowerment is perhaps best called maturity.

Her final step is to free herself from oppression in a scene of literal and figurative knocking off. In his commentary, Kent Jones says the climax reminds him of GONE TO EARTH, thought I personally see a strange echo of BLACK NARCISSUS.

It's an idea typical of its era of sexual liberation that Cora's freedom should come about though posing naked, albeit without apparently sexual objectification, since the artist is interested in that spiritual line between the naked and the nude. The title refers to Ma Ryan's nasty, blackmailing threats of how the law would perceive the relationship even though it's sexless - at least it is until the very end, after Bradley has come to his own self-awareness. The title also implies that the age is a personal one and that it even applies to Bradley, the age when he consents to renew his life. Jones says Mason wanted the romantic ending and that Powell might have done it differently on his own.

Australia is supposedly looser than the US, or so we've sometimes heard, but on this side of the Pacific almost 40 years later, even the non-sexual relationship in the film would be problematic in our cinema and under our mores of the appropriate. (This is mitigated by the fact that we never learn what the age of consent is in that time or place, or how old is Cora, and that Mirren is in her 2Os.) This may mean that the film's liberated vision is either out of date or still ahead of its time.

That vision, though translated by Powell and writer Peter Yeldham. originated with Australian artist Norman Lindsay, upon whose popular novel this was based and whose authorial credit is trumpeted above the title. Jones describes Lindsay's cultural-artistic position in Australia as a combination of Norman Rockwell, Alberto Varges and Maxfield Parrish, which isn't altogether impossible to imagine after seeing the film.

Cinematographer Hannes Staudinger provides the strong color-sense we associate with Powell's color cinema, with a natural emphasis here on blues and yellows. Although this color is necessarily of a different quality from the previous film's Technicolor, the outdoor scenes shimmer and Bradley's painted objects stand out vividly in this wonderfully sharp restoration. There's also beautiful underwater photography by Ron & Valerie Taylor.

Co-produced by Columbia, this was a big success Down Under but not in the US, where it was notably altered. At least some nudity was removed, including the opening credits with their artistic gag on the Columbia logo, and Peter Soulthorpe's pretty gamelan music was replaced by a Stanley Myers score. (That alternate version might have made an instructive extra, but it would have meant another music clearance.)

The pairing of these two films is revealing; although superficially unalike, they have similar currents. The heroes of both films are creators at the high-culture end of art (poetry, painting). Both men are drawn to younger women who embody purity and the hopeful future, and both films argue that love takes priority above law. Just as the beached Carter's fist encounter with another soul was the mythically naked shepherd-boy, so Morahan encounters a mermaidish girl on a beach, where she will spend much time nude.

Christie points out the link between Dr. Reeves with his camera obscura, and Prospero with his "mirrors and devices" in THE TEMPEST, an unmade dream-project of Powell's that recurs subliminally in his films much as the ghost of

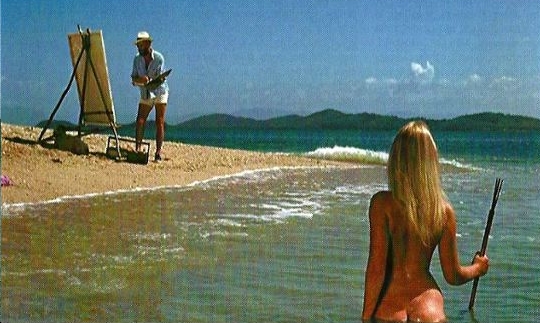

While on Australian holiday, artist James Mason discovers a new Muse

in the form of Helen Mirren in Michael Powell's final feature, AGE OF CONSENT

|

James Barrie's play MARY ROSE, Alfred Hitchcock's dream-project, lurks in that artist's output. Reeves is also a figure for Powell, "directing" the villagers on his screen and later directing Carter's case and uniting its double narrative. Reeves' dogs are in fact Powell's. if Powell saw himself as a Prospero-like magician, it was unfortunately prophetic of his later career "exile" after PEEPING TOM. Just as THE TEMPEST was Shakespeare's final play, AGE OF CONSENT turned out to be Powell's final feature and is the closest he got to filming Prospero's tale. Bradley is his island's aging, reclusive, creative wizard, with paintbrushes for wands, but he is a self-exile rather than a man betrayed. Jones says Powell at one point wanted to end the film with Bradley turning to the cameramen and declaring that he's given up painting for photography in order to make films like this one, a gesture that would certainly seal the identification. Jones also points out that this last feature is an island film, as was the film Powell considered to be his personal debut, THE EDGE OF THE WORLD. It's also a secret collaboration with an uncredited Pressburger, whom Powell at least consulted.

These movies make their US disc debut thanks to The Film foundation, which released THE FILMS OF BUDD BOETTICHER a few months earlier. It would be churlish to complain that the Boetticher set had five movies while we're still waiting for many other Powells; instead, we're grateful that these restorations finally provide Yanks and other Region 1 types with lush copies of two films from the catalogue of a major film artist. Martin Scorsese offers an intro for each movie. Other bonus segments only accompany the later title, for which a making-of (17m) interviews Kevin Powell (Michael's son), editor Anthony Buckley, and Sculthorpe. There are separate, charming interviews for Mirren (12m) and the Taylors (10m). The 1946 film is fullscreen while the later is presented in anamorphic 1.85:1. Both offer English and French subtitles.

Pictures from the PaPAS Gallery

Other reviews