|

Suddenly Michael Powell is back where he belongs, accepted without question as one of the greatest British film directors, reinstated in the pantheon of giants of the cinema. He is interviewed all over the place, gets his very own edition of the South Bank Show and delivers lectures to avid, admiring audiences of cineastes, most of whom were born long after the days when he was in full creative flood.

The reason is a magnificent, immense and immensely readable autobiography, A Life in Movies, which, in spite of running to nearly 700 pages only takes him up to 1948 when he was 43 and with his long-time partner, Emeric Pressburger, had just made one of the landmark films in cinema history, The Red Shoes.

The second volume is in preparation and ought to be even more fascinating because it will deal with the days of obscurity that followed his 1960 film, Peeping Tom, a horror tale about a photographer who killed his subjects. It was savagely attacked by the critics, and the public did not like it much either, although the passage of time has given it cult status and the verdicts have been revised. But the result was that Powell, already saddled with a reputation for being a big spender, was cast out into the wilderness.

He has never understood why the attacks on Peeping Tom were so viscous and virulent. But the outcome, he said, when we talked about the book in his London hotel, was that he found it impossible to raise money to make more films. He went to Australia, worked there for a while, and did some television, but his career was on the wane. It has never recovered. He is not, however, bitter and his book manifestly is not the work of an embittered man, rather of one who enjoys living to the full.

At 81, Michael Powell is a small, spry and dapper man. His brown shoes were polished to that mirror sheen favoured by elderly military men, and his bearing has prompted interviewers to liken him to Colonel Blimp, the hero of one of the finest Powell and Pressburger films, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Perhaps the analogy is apt. But he is far more quirky.

The film was chosen to launch British Film Year in a spanking new print, and the famous pair turned up for the occasion. Powell did not mince his words. He is a great believer in internationalism in the cinema, and pointed out that it had been written by a Hungarian, designed by a German, photographed by a Frenchman and - one need not go on. Sucks to British Film Year as an insular concept.

He is skilled at telling his tale, but does so, as he does in the book, in a highly discursive fashion. The tale is begun, dropped, a diversion or two brought in, and then returned to. There are off-putting pauses. But when he gets there the journey turns out to have been immensely satisfying.

The nice Scots lady from Hienemann [sic] warned me when arranging the meeting that he can be difficult, and dispatched an interview from Books and Bookmen to guide me on what areas to avoid. It was obvious from it that Powell and that interviewer had not been seeing exactly eye to eye, as the latter's attempt to find out his views on Hitchcock show. Powell worked with Hitchcock at Elstree while he was making The Lodger and Blackmail, the film to which Hitchcock added sound and made history.

'Hitchcock was determined to make his own films, the kind only he could make, and the only kind he could make.'

In the book he claims to have first suggested what was to become the other man's trade mark - the climatic chase in some bizarre setting like the Statue of Liberty, the tower of Westminster Cathedral or the faces on Mount Rushmore. Modest Powell is not. He says that for The Lodger he suggested a chase through the Reading Room of the British Museum ending with a fall through the glass dome. [It was for Blackmail]

But to the story. Asked by the Books and Bookman interviewer - "You worked with the early Hitchcock?" - Powell replied in no uncertain terms that he didn't care about the early Hitchcock.

I fared rather better than that, and when I at last got him on to the subject of Hitchcock he said he had worked with him for a year in 1928 and he had obviously been the brightest director around at the time. "He was determined to make his own films, the kind only he could make, and the only kind he could make," he said. It is a splendid back-handed compliment, as well as being very perceptive.

|

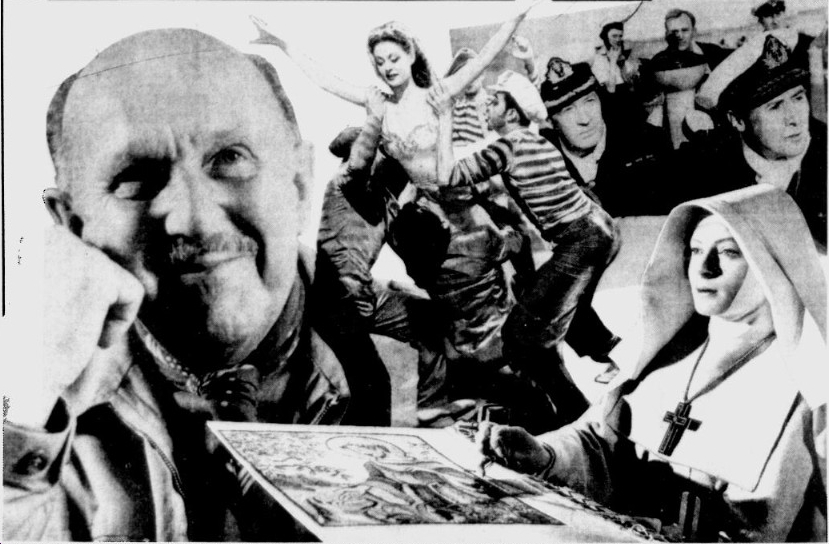

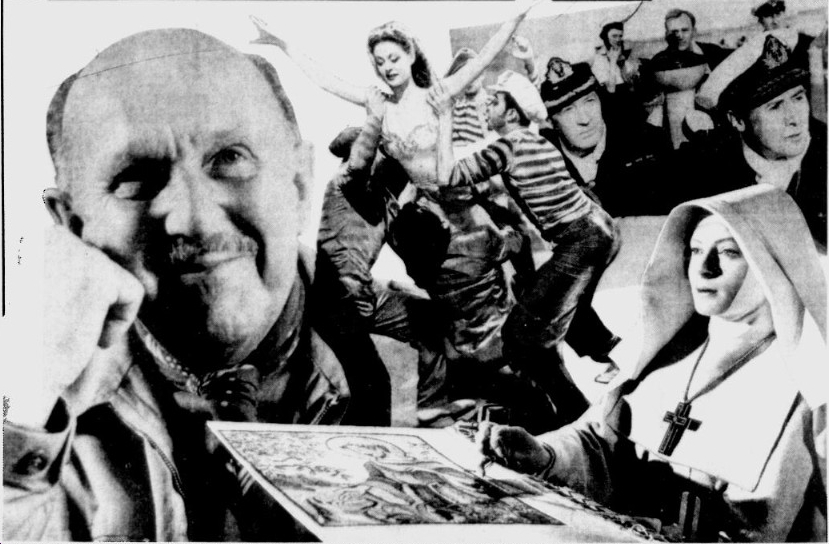

Michael Powell, the cocksure young director who turned rebellious guru, with some of his cast of thousands. They include devout Deborah Kerr in The Black Narcissus [sic], Moira Shearer in the ballet film The Red Shoes, and Brits on the bridge in The Battle of the River Plate.

The life and times

of Michael Powell |

|

Powell said that A Matter of Life and Death - it was the first royal performance film - was the most complicated he had made and to this day astonished film makers. It was the one he most enjoyed making. "It is a big fantasy," he added. "A Big Film with wonderful actors - not big stars. Raymond Massey, Roger Livesey, David Niven, all wonderful, big personalities. It is full of camera tricks of all kinds and they all seemed to come off. They seemed to come off easily. Everybody had as much fun out of making it as I did. Everybody shared in this cosmic joke."

The book contains a fascinating account of another trick, how he created the Corryvreckan whirlpool in I Know Where I'm Going, one of his two Scottish films, - "one of the best I eve made" - which is set in the Western Isles. It comes down to watching the bathwater going down the plughole.

Perhaps he had in mind Gone to Earth, a lush David O. Selznick production starring Mrs Selznick to be, Jennifer Jones, of the Mary Webb novel, set in deepest Shropshire, or possible a dastardly piece, The Elusive Pimpernel, which they made at Korda's behest, starring David Niven. His relationship with Korda was complex. Powell was, by the way, co-director of The Thief of Bagdad, one of Korda's greatest successes.

Powell has no love for the money men, and both J. Arthur Rank and his sidekick John Davis, come out of the book badly. Rank, he said was puzzled by I Know Where I'm Going, and a little reassured by A Matter of Life and Death. But neither he nor Davis could make anything of The Red Shoes and he walked out of the cinema when it was shown to them.

"I honestly do not understand businessmen," he added. "The trouble with films - the theatre is all right, because the businessmen there are showmen - is that you are dealing directly with financiers and they always want you to do what you have just done. They were genuinely frightened by The Red Shoes. It was not going to make money, they said. The public understood nothing about art.

"To this day they probably do not know that the public is well ahead of them all the time. Looking back I do not think the public ever let me down. But the film financiers let me down."

The book is crammed with anecdotes, all revealing, about famous names, many about the stars he and Pressburger created - the same people perform for them over and over again. Livesey, Byron, Shearer, John Laurie, Pamela Brown, Marius Goring, Anton Walbrook, Esmond Knight, David Farrar and Sabu.

He has a deep affection for Scotland. Alistair Dunnet, the former editor of The Daily Record and The Scotsman, is a friend, and over the years they have walked in the Highlands together. His most personal film is perhaps his story about the evacuation of St Kilda, The Edge of the World, made actually on Foula and shot in 1937 [Shot in '36, released in '37] with John Laurie leading the cast. He owns the negative and US Cable television is currently trying to persuade him to let them show it.

'He adores doing the daring thing, taking risks, making the big, bold, extravagant gesture.'

Powell was rescued from obscurity by Francis Ford Coppola, who invited him to join the producers and directors at his Zoetrope studios. That venture, however failed through lack of finance. Powell told me a story related to him by George Lucas, another friend - he has found ardent admirers in Hollywood, including in addition to Coppola and Lucas, Scorsese, and Spielberg.

According to Lucas, if there was a fire at Zoetrope he would sneak out by the fire escape, Coppola would jump off the roof. Powell, I suspect, would jump too. As his films show he adores doing the daring thing, taking risks, making the big, bold, extravagant gesture. He is an egomaniac and a cynic who loves life.

(Michael Powell and his third wife Thelma Schoonmaker, will be at the Filmhouse, Edinburgh, on Thursday, and at the Glasgow Film Theatre on Friday to talk about his career following screenings of Gone to Earth. A Life in Movies is published by Heineman at £15.95.)

|

|

His summing up of the director Victor Saville, is equally to the point as being someone who would never make an unsuccessful film, nor direct a good one.

But back to Hitchcock. "We were friends all our lives," he said. "But I always felt he was - I was always coming up with something new, he was always coming up with a suspense film. He was playing the game in Hollywood of star power and more and more in his films he turned to big stars. It was very clever, but then you start working for the stars. I like to tell the story the way I see it. It is a fundamentally different approach.

Hitchcock, he added, was "a very shrewd Cockney," a director whose view of people fitted into the American pattern very well.

He said he had not written a book to pay off old scores although that had not stopped him doing so, nor from disclosing a lot about his love life as well. Rather he had written it because he had decided the history of the British cinema had not been properly recorded, and he, one of those who had lived through and made a job of it, was the person for the job.

Then he asked had I noticed it had no pictures. I had, but before I could enlarge on it he told me that some interviewers had complained and he in his turn complained that they had missed the point. His book was divided into three sections - separate books entitled Silent, Sound and Colour. What was it they wanted - coloured pictures?

'I came into films with no patronage, no money, nothing. Just the love of the art.'

What I am describing is going from silent films to sound and from sound to colour," he said. "You can write about that, but if you put in a lot of black and white stills you beg the question."

His publishers took the point. His words have been left to tell his story.

He said he had meant it to be one big book, but there were going to have to be two big books. Not that he is daunted. Thinking big is a Powell trait. He regards My Life in the Movies [sic] not as a show business tome, but more like an eighteenth or nineteenth-century picaresque novel.

It was aimed, he added, at young people, not old people. As for being old himself, he did not feel old. He felt young. "If I can explain, set down what it was like for a young man to put his whole life into this extraordinary new art, I am sure it will give them - the young - a big push," he said. "I came into films with no patronage, no money, nothing. Just the love of the art."

He paused, and then added firmly - "That should be particularly acceptable to the Scots."

Chateaubriand was the model he adopted in writing it, he said. And just in case I was surprised reminded me that French was his second language. He began his career working for Rex Ingram at the Victorine studios near Nice, and almost forgotten episode in British cinema history which he recalls lovingly in the book. Chateaubriand had, he said, hit on the idea of always being present in the past, of guiding and making clear what happened when and where. And it is how he has shaped the book.

"I started it as a novel, wrote about 60,000 words and after a year threw it away," he said. "I decided I had to write a book on the cinema. I do not think anyone else is alive who can - those who are do not want to, or cannot."

At one point I told him - we had been ranging over the Powell and Pressburger canon, the years when the pair could do no wrong - that I had grown up on their films. He seemed delighted, grabbed my hand, shook it, and said that he had never thought of it like that. But it is true. A whole generation of British cinema goers were raised on their films.

The titles are as evocative as any list of Hollywood's golden greats, and the range - for they are the work of the same two men - is starting. 49th Parallel, One of Our Aircraft is Missing, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, I Know Where I'm Going, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, The Small Back Room, The Battle of the River Plate and The Tales of Hoffman [sic], many made for their own company, The Archers, with Powell directing and Pressburger writing the scripts.

|

The book is splendidly indiscreet. His affair with Deborah Kerr is one example, quite shattering the image that genteel and delightful lady has assiduously fostered over the years. She first worked for him in Contraband, a thriller starring Conrad Veidt. Her part ended on the cutting room floor, but Powell recalls she played "an adorable little cigarette girl" ... "all lovely liquid eyes and nice long legs" and regrets the clip has long been lost.

Her big break came when he cast her as the three women in Blimp's life. Of their relationship he writes - "I learnt from Deborah what love is." He asked her to marry him in a bid to stop her going to Hollywood - she went - much to the ire of his companion, Frankie Reidy, who was, in fact, to become his wife, but who, in spite of having lived with him for 10 years had not at that point made up her mind whether she wanted to or not. In the book he says it was perhaps tactless of him to tell her about Miss Kerr in bed.

The man, it is clear, is something of a bounder. He discloses that by the time Miss Kerr starred in Black Narcissus he had another mistress, Kathleen Byron, who played the neurotic, sex-starved nun, a situation he clearly enjoyed. I asked about the revelations in the book and he sighed gently - "Ah, Deborah. That was a real love affair. I hope she will not be offended. But I had to write it as it was. That kind of honesty may surprise and shock some people, but I don't think so."

At one point in the book he refers to his first marriage, and somehow the passage sums up the man. It is, therefore, worth quoting.

"Her name was - but what does it matter what her name was," he writes. "It lasted just three weeks. She was beautiful, young, strong, healthy, American - and just about the last person to be made happy by me, and vice versa.

"In 1927 I was slim, arrogant, intelligent, foolish, shy, cocksure, dreamy and irritating to any sensible woman who had her fortune to make, a family to plan. Today I am no longer slim."

'We did not seem to be able to find the challenging subjects we had done under the pressure of war.'

He first worked with Pressburger, a Hungarian who had fled Nazi Germany, in The Spy in Black, another Veidt film made in 1939. Pressburger had been called in by Alexander Korda to doctor the script, and ended up rewriting it totally. The only thing left when he had finished of the J. Storer Clouston novel was the title. "Wasn't it wonderful the way he turned it upside down," Powell said, the tone being that of a man who enjoys doing precisely that himself.

Why did the partnership break up? That will presumably be revealed in volume two, but somehow, it seems, they lost their way. "It all started to fall apart after the war," he said. "'We did not seem to be able to find the challenging subjects we had done under the pressure of war. More and more we turned towards filming books. That was a mistake."

Whatever the reasons, there is no denying the portrait of Pressburger in the book is affectionate. Powell said that what his partner wanted to do was to write novels and plays, and that he had always been a novelist at heart, whereas he, Powell, had been a film maker.

He is obsessed with the tricks the camera can pull, and immensely proud of Black Narcissus, which was filmed in the studio at his insistence and is a brilliantly designed film, one which has been composed throughout. He then told me a story about how Bernardo Bertolucci, currently filming in China, the story of the last emperor who ended up as a gardener in his own palace gardens, had only just caught up with A Matter of Life and Death. He had told Powell that it contained three tricks that he had been hoping to pull off himself.

|